LEOŠ JANÁČEK

(1854–1928)

Although in terms of age Leoš Janáček is more part of Antonín Dvořák's generation, his music is some of the most expressive to be found in the 20th century, placing this composer among musicians two generations his junior. Janáček's life and work are closely connected with Brno, where he lived from childhood and where his tireless work as a composer and organiser contributed greatly to the development of Brno's cultural life.

Leoš Janáček was born on 3 July 1854 in Hukvaldy, the ninth of fourteen children, to the Hukvaldy teacher Jiří Janáček and his wife Amálie, née Grulichová. When recalling his childhood he mentioned the school in Hukvaldy, his father's beehives, the Babí hora hill and the church gallery where he sang at ceremonial masses. He was an average pupil at school, but showed uncommon musical ability. His father's worsening health and a shortage of money led the parents to seek an education for their son using a scholarship for musically gifted boys from poor families in Kroměříž or in Brno. Janáček's father became friends with the composer and director of the Brno foundation, Pavel Křížkovský, so they opted for the Augustinian Monastery in Old Brno. The eleven-year-old Leoš left for Brno in August 1865, bringing his childhood to a sudden end.

I had been accepted as a chorister in both Brno and Kroměříž and father selected Brno. I had a fearful night with my mother in a kind of dark chamber - this was on Kapucínské náměstí.

Me with my eyes wide open. At first daylight, quick, out!

Mother left me with a heavy heart at the Klášterní náměstí.

I had tears in my eyes, so did she.

Alone. Strange people, unkind,

a strange school, a hard bed, even harder bread. No caresses.

My world was built exclusively by myself. Everything fell into it.

My father died, the ill-considered cruelty.

A View of the Life and Works (1924)

Leoš Janáček

in 1874

© Moravian museum

There were many important figures to be found at the Augustinian Monastery, including the composer Pavel Křížkovský, the father of genetics, Johann Gregor Mendel, and the enlightened abbot, Cyril Napp. The boys from the Old Brno foundation, who were nicknamed the bluebirds, were given a thorough musical education linked to singing at the masses at the basilica of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, music at the monastery, as well as concerts and opera performances in Brno. Almost fifty years later, Janáček recalled his life in the monastery in his composition The March of the Bluebirds from the wind sextet Youth.

The Augustinian Monastery not only gave Janáček a good musical background, but it also equipped him with a thorough all-round education. He attended the German grammar school in Old Brno from 1866 to 1869, and the Slavonic Teachers' Training Institute from 1869 to 1872. Just as Janáček's father had wished for his son, the way was now clear to becoming a teacher. However, in the same year that he finished his studies, the director of the Old Brno choir, Pavel Křížkovský, left for Olomouc and Janáček was asked to take his place in his absence. Janáček agreed and a year later also became the choirmaster of the Svatopluk craftsmen's society chorus (1873-1876). He began to compose at this time, writing the male choruses Ploughing and The Fickleness of Love in the style of his great mentor, Pavel Křížkovský. In addition, the young Janáček decided to broaden his musical education at the Prague Organ School, and so he slowly moved away from his predetermined career as a teacher.

The entrance exam at the boarding school in Prague - in the Organ School.

Professor Blažek: "How is a dominant set out - a seventh chord?!"

Silence.

"A seventh steps down, a third goes up, a fifth rises, the tonic falls.

He doesn't even know that."

In my head went:

And the seventh did not step down, the fifth didn't rise and the tonic didn't fall! From that time I began to think about the mystery of combining chords.

A View of the Life and Works (1924)

And it was during his studies in Prague that Janáček's forthright, sometimes even conflictual character, came out. In the journal Cecílie he published a review of a Gregorian mass that had been conducted by the headmaster of the Organ School, František Skuherský, where he criticized the deficiencies in the chorale performance, and as a result was immediately suspended from the school.

I will remember this day for I was wronged for telling the truth.

Janáček's entry in his exercise book

Leoš Janáček

in 1882

© Moravian museum

In the end, following the intervention of Pavel Křížkovský, he was able to finish the three-year course in just one year and with excellent marks. His stay in Prague also marked the start of Janáček's long-term friendship with Antonín Dvořák. After returning to Brno he taught at the Teachers' Institute, dedicated himself to the organisation of Brno's concert life, composed, conducted and led the choir of the Philharmonic Society of the Brno Beseda (1876-1888). Under Janáček the Brno Beseda became an important ensemble, performing works which included Mozart's Requiem, Beethoven's Missa solemnis and Dvořák's cantata Stabat mater.

At the end of the 1870s, Janáček started giving piano lessons to the daughter of his boss, Emilian Schulz, the headmaster of the Teachers' Institute. A relationship quickly developed between the 25-year-old Janáček and the young Zdenka. In 1879 Janáček left Brno for the Leipzig and then the Vienna Conservatory, and even though he was later to recall that "there was nothing to be learned here", it is certain that the young composer became thoroughly acquainted with German romantic music during his numerous concert visits, and he had the opportunity to hear wonderful pianists such as Clara Schumann and Anton Rubinstein. However, he did not forget about his Zdenka, and out of the numerous compositions he wrote in Leipzig he dedicated to her Zdenka's variations for piano, which at the time he considered to be his best work. He also wrote to her often, sometimes several letters a day. He described his student life thoroughly, but he also confessed his innermost feelings.

My dear, kind Zdenka, I can only see happiness in the future if I strive to prepare the most beautiful future for you, please keep this belief strong within you...

A letter to Zdenka Schulzová (13. 10.1879)

Zdenka Janáčková in 1885

© Moravian museum

Not long after his return, Janáček married Zdenka Schulzová in 1881, but the beautiful future which he had promised did not transpire. The first serious crisis came shortly after the wedding, which was not smoothed by the birth of their daughter Olga and continued for many months. In the end, the relationship was settled, but the marriage was never completely happy again.

At this time, Janáček was incredibly overloaded with work. In addition to all of his previous duties he now held the position of headmaster and teacher at the Organ School, which he established in 1881.

The idea behind the Brno Organ school is mine and one which I've been fully committed to since I was capable of independent thought. I travelled to my studies in Prague with this idea and I see its realization as one of my greatest tasks.

A letter to Zdenka Schulzová (29. 11. 1879)

Along with his compositional work and teaching duties he also set up and edited the journal Hudební listy (1884-1888) and wrote specialist articles and reviews. Thanks to his talent, tenacity and uncommon work rate, he went from being a poor choral scholar to becoming a respected figure in Brno.

From 1887 to 1888 Janáček wrote his first opera, Šárka, to a libretto by Julius Zeyer. However, due to his anti Smetana position, he was disliked in Prague and Zeyer refused to give him permission to use his text. Therefore, he had to set aside his work on this opera and he did not return to it until 1919. Even though it was his first attempt at an opera, the composer still thought highly of it some thirty years later.

My Šárka? Everything within it is so similar to my last work!

A View of the Life and Works (1924)

After this failure and the dramatic rupture with the Brno Beseda, he plunged himself into the study of folk music in 1888. Janáček's interest in folk culture can be seen through A Bouquet of Moravian Folksongs, which was published in 1890, and it was also apparent in the compositions he wrote at the time, such as Lachian Dances, Folk Dances in Moravia, The Little Queens and the ballet Rákoš Rákoczy. Janáček also wrote his second opera The Beginning of a Romance, which he himself conducted in 1894 at Brno National Theatre. Janáček later reflected on this minor work, the text of which was naive, verging on simpleminded:

The Beginning of a Romance was an empty comedy; it was tasteless to force me to put folk songs into it. Because it was just after Šárka! Listen to this example that I had to compose to!

Poluška: I have never known a kinder man.

He never uttered a bad word -

God heard him and the grove and the forest -

and asked that I come today.

A View of the Life and Works (1924)

At this time there was also a tragedy within the Janáček family, when in 1890 their two-year-old son, Vladimír, died suddenly. The Janáček couple became even more estranged.

Beside each other, shared unhappiness, shared pain, and then each of us so alone...

Memoirs: Zdenka Janáčková - My Life (1998)

Despite everything, Janáček remained very active in public. He became a member of the committee of the Cooperative of the Czech National Theatre in Brno, his love of Russian culture led to the establishment of the Russian Circle, and he later also became chair of the Club of Friends of Art.

In 1894 he decided to write an opera based on a work of prose of the first composer to do so. He chose Gabriela Preissová's realist play Her stepdaughter. He worked on it for nearly ten years, employing a completely new compositional approach, which with its innovation and uniqueness transformed this provincial composer into one of the world's leading composers. We do not have an unambiguous answer to the oft-answered question of what inspired this work which was so different from the rest. However, Janáček's new compositional approach was linked with his interest in speech, which reflects the psychological state of the individual and the mood of the moment. Janáček was convinced that it was objectively possible to record people's speech using musical notes.

He began writing down these speech melodies, as he himself called them, in 1897, and continued to do so for the rest of his life. However, he not only recorded speech melodies; amongst more than four thousand notations we also find the melodies of dogs barking, the buzzing of mosquitoes and the creaking of wooden floors.

Speech melodies are an expression of the organism's entire state and all the spiritual phases which emerge from it. They show us if a person is either stupid or sensible, sleepy or drowsy, tired or lively. They show us a child or an old man; morning and evening, lightness and darkness; heatwave or frost; loneliness or society. The art in dramatic compositions is to insert speech melodies which, as if by magic, immediately reveal a human being at a certain stage in life.

This Year and Last Year 3 (Hlídka XXII, 1905)

Olga Janáčková in 1902

© Moravian museum

Janáček completed his opera Jenůfa in February 1903, one of the saddest times in his life, when Janáčeks lost their second child, beloved daughter Olga, who died aged twenty-one.

I would bind Jenůfa with a black ribbon for the long illness, pain and laments of my daughter Olga and my little boy Vladimír.

A View of the Life and Works (1924)

Leoš Janáček

in 1904

© Moravian museum

Shortly afterwards he offered Jenůfa to the National Theatre in Prague, but it was not long before they returned the opera together with a brief note from the head of the theatre saying that the work could not be accepted. This was a great blow for Janáček. He became depressed and felt a creative impotence. Jenůfa was accepted by the National Theatre in Brno, and even though the premiere on 21 January 1904 was a success, this was more regional in character. In the same year Janáček also asked for early retirement so that he could concentrate on his Organ School and composition. This period was also when he started to make regular visits to the spas at Luhačovice.

What was I looking for in those spas? Thirty to thirty-five to forty hours a week teaching, conducting the singers of the association, organising concerts, in charge of the organ loft at the Queen's Monastery, whilst writing Jenůfa, getting married, losing my children − I needed to forget myself.

A View of the Life and Works (1924)

During one of his visits to Luhačovice he met Kamila Urválková, whose life story inspired him to write the opera Fate.

And she was one of the most beautiful ladies. Her voice was like a viola d'amore. The Luhačovice Slanice lay in the heat of the August sun. Why did she walk about with three fiery roses and why did she tell me the story of her young life? And why was the end so strange? [...] And a mournful work just by its tone, and female by its words, entitled Osud - Fatum.

A View of the Life and Works (1924)

Leoš Janáček in 1906 in Luhačovice © Moravian museum

The opera set in the spas of Luhačovice was given to the Vinohrady Theatre, but it was never performed. This was due to the demands placed on the orchestra and singers, who even signed a petition stating that they didn't want their roles in Fate to ruin their vocal chords. The problematic libretto was also somewhat to blame. It was to be the only opera by Janáček which was to remain unperformed during his lifetime. However, from a musical perspective Fate is one of Janáček's most remarkable works and it is interesting to note that the composer used the historical instrument, the viola d'amore, for the first time, which was to appear in several other compositions.

An important moment in Leoš Janáček's artistic development was when he came across the poems of Petr Bezruč, who he felt an affinity with through his social themes.

Your words were like a calling. And I took from them tones of tempestuous rage, despair and pain.

A letter to Petr Bezruč (1. 10. 1924)

He dedicated the choruses Halfar the Teacher, Maryčka Magdónová and The 70,000 partly to the new Moravian Teachers' Choir, which he was to lead for a short while in many places around Europe. However, Janáček's greatest wish that Jenůfa would finally be performed in Prague remained unfulfilled.

I do not want my repeated request that Jenůfa be heard on the stage of the National Theatre in Prague to be based on flattering Prague reviews, not to mention the local ones. My only complaint is that it was unfair to reject Jenůfa. This is a complaint from a Czech composer whom no-one would grant a hearing.

A letter to Karel Kovařovic (9. 2. 1904)

Janáček began to believe in himself even less. He destroyed some of his works, such as the piano composition 1. X. 1905 (From the Street) and the autograph of Jenůfa.

I didn't value my work, just as I didn't value what I said. I didn't believe that anyone would notice anything. I was defeated - even my own students were advising me on how to compose, write for the orchestra. I laughed at this - there was nothing else I could do.

A letter to Josef Bohuslav Foerster (24. 6. 1916)

Janáček celebrated his sixtieth birthday in 1914 on the sidelines as a misunderstood provincial composer. However, that would all soon change.

Leoš Janáček in 1917 in Luhačovice

© Moravian museum

Thanks to the diplomatic efforts of the chair of the Brno Club of Friends of Art, František Veselý, and his wife, the writer and singer Maria Calma, the director of the National Theatre, Gustav Schmoranz, and the conductor Karel Kovařovic agreed to perform Jenůfa at the National Theatre in Prague. Janáček agreed to Kovařovic's condition that parts of the opera had to be changed, which meant that the work was greatly altered, especially in terms of instrumentation. And as a result the grand Prague premiere could take place in May 1916. Until that time Janáček was practically unknown and unappreciated, and then at the age of sixty-two he appeared as a composer with an original approach towards musical drama without pathos and cheap effects, which we are familiar with from some verist operas. At around this time Leoš Janáček also began a close relationship with the Prague Kostelnička, Gabriela Horváthová, as well as starting a friendship with Max Brod, who "arrived at the right time as if sent from heaven". Brod brought Jenůfa to the attention of the management of Universal Edition publishers and translated the opera into German. The Court Opera in Vienna also showed interest in Janáček's opera, performing it in February 1918. This marked the start of Janáček's worldwide fame. It is also interesting to note that the Metropolitan Opera in New York performed Jenůfa as far back as 1924. After the Prague premiere of Jenůfa, Janáček completed the rhapsody Taras Bulba and the opera The Excursions of Mr Brouček.

The foundation of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918 was welcomed by a Janáček full of strength and plans for the future.

I have arrived here with the youthful spirit of our republic, with youthful music. I am not one of those who look back, rather I prefer to look forward. I know that we have to grow, and I do not see this as growing pains, as memories of suffering and oppression. Let us cast that off. We are a nation which means something in the world. We are at the heart of Europe. That heart has to be felt in this Europe!

From Janáček's speech given in London in 1926

Leoš Janáček and Kamila Stösslová in Luhačovice in 1927 © Moravian museum

The last decade of Janáček's life was the most creative period in his life. The uncommon dynamic of creativity and energy which the elderly Janáček displayed is a mystery which Janáček himself addressed in one of his letters to his friend Kamila Stösslová. Janáček met the then twenty-five-year-old Kamila in 1917 and their friendship continued until the composer's death. For Janáček she was a source of inspiration, an ideal woman, and it mattered little that the reality was somewhat different

.

And people? They roll their eyes; I'm so successful, there's vigour in my compositions. Where does he get it from? A mystery. It burrows within them like a mole as they try to solve it. I would be so happy to shout out, lift you up, point to you, "Look, my dear, charming mystery in life!"

A letter to Kamila Stösslová (12. 3. 1928)

Without doubt this creative period was the most productive in Janáček's life. In 1920 he wrote the symphonic poem The Ballad of Blaník and he finished the opera Katya Kabanova a year later and started work on his next opera The Cunning Little Vixen.

I captured the cunning little vixen for the forest and for the sorrow of one's final years. A merry thing with a sad ending, and I too am standing at that sad end.

A letter to Kamila Stösslová (3. 4. 1923)

In 1923 he finished the first string quartet After Tolstoy's Kreutzer Sonata and wrote an opera based on Karel Čapek's The Makropulos Affair. He went to the international festivals organised by the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM), where he stood alongside the young avantgarde artists, and went on a tour of England.

In 1925 he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Masaryk University, the first in the institution's history, and two years later was appointed a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences along with Arnold Schoenberg and Paul Hindemith, and in the same year King Albert of Belgium conferred upon him the Order of King Leopold (such was the impression made by the success of Jenůfa in Antwerp). The Capriccio from 1926 for piano one hand and chamber ensemble was dedicated to the pianist Otakar Hollmann, who lost his right arm during the First World War, and was the first in a series of compositions written by several international composers for war invalids. In the same year Janáček wrote his most famous orchestral work, Sinfonietta, which he dedicated to "his town" of Brno, as well as the no-less-famous Glagolitic Mass.

Without the gloom of medieval monastic cells in its motifs, without a trace of clichéd imitative procedures, without a trace of Beethovian pathos, without Haydn's playfulness; against the obstacle of Witt's reforms - which estranged Křížkovský from us! Forever the scent of the mild Luhačovice forests - this was incense to me.

Glagolitic Mass, Lidové noviny 1927

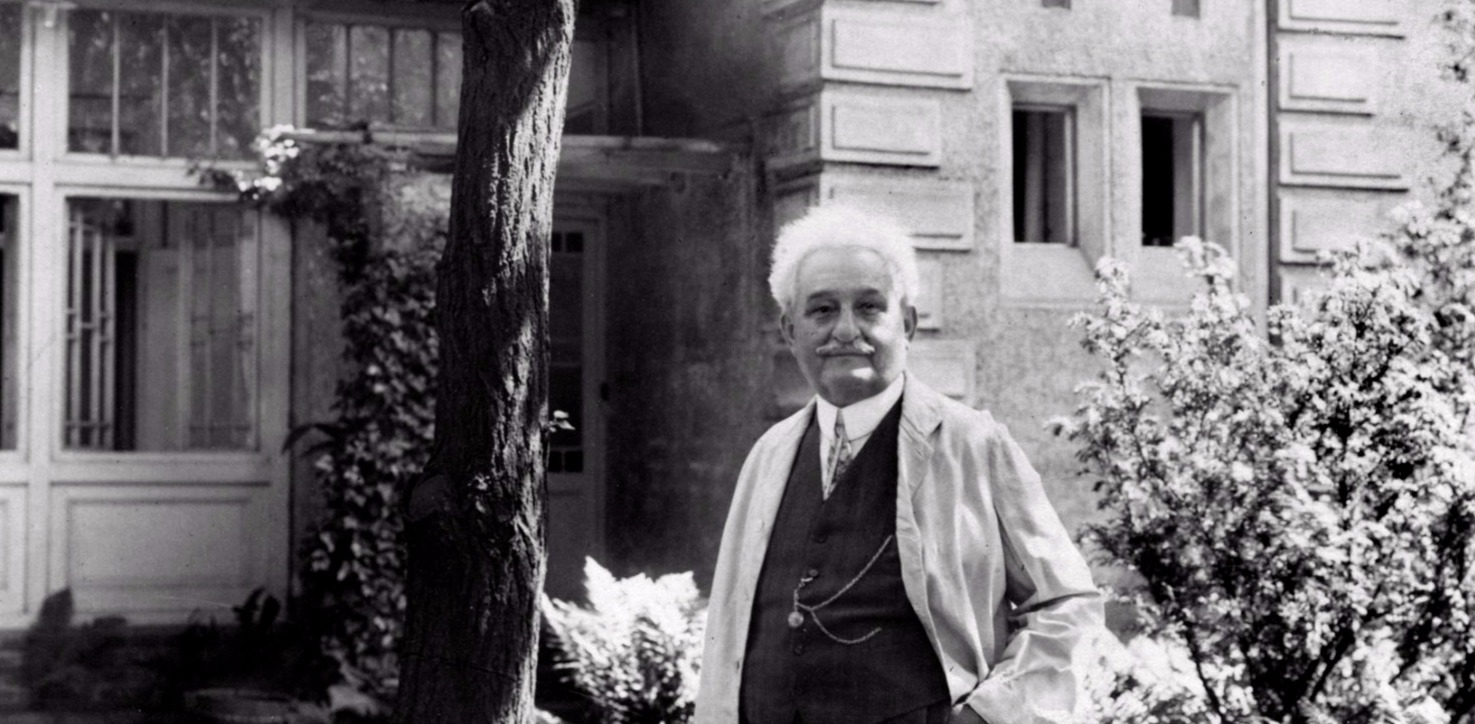

Leoš Janáček in 1926 © Moravian museum

The older Janáček became, the more progressive and youthful his music was. It came from a man who was full of energy and strength. When following the Brno premiere of the Glagolitic Mass Ludvík Kundera wrote in his review "Janáček the old man, a man who is a strong believer," the composer wrote back to him succinctly: "None of this old man or believer, young man!"

In the final year of his life he worked on the opera From the House of the Dead based on a novel by Dostoyevsky, which he himself translated from Russian and adapted into a libretto. He also composed his string quartet no. 2 Intimate Letters, which was a kind of personal musical diary dedicated to Kamila Stösslová.

I've just started writing something nice. It will have our life in it. It's going to be called Love Letters... The whole thing will be held together by a strange instrument called the viola d'amore - the viola of love. I'm so looking forward to it! In this work I will always be together only with you! No third person beside us. Filled with that longing, like with you there in our heaven. I will be so happy to do it! For you know that I know of no other world than you! You are everything to me, I want nothing more than your love.

A letter to Kamila Stösslová (1. 2. 1928)

Leoš Janáček

in Prague Bertramka in 1928 © Moravian museum

At the end of July 1928 Janáček left for Hukvaldy, followed by Kamila with her son Otto. He took with him the score for From the House of the Dead in order to make changes and additions. However, he never managed to finish his work. He caught a severe cold and was taken to the sanatorium of Dr Klein in Moravská Ostrava, where an X-Ray showed he had caught pneumonia. He died on Sunday 12 August at 10am in Ostrava, and three days later one of the most remarkable composers of the twentieth century was buried at Brno's Central Cemetery. He died when the Czechoslovak Exhibition of Contemporary Culture was coming to a close at the newly built exhibition grounds, when the city was experiencing a fame which Janáček had greatly contributed to.

The Brno of today still stands on the cultural foundations laid by Janáček. During his lifetime the Organ School became the Brno Conservatory, the Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts was established in 1947, nine years later the Brno Philharmonic was founded and in 1965 the new modernist building of the Janáček Theatre was opened. Since 2004, Brno has hosted Janáček Brno, an international opera and music festival, and in the near future a Janáček Centre will be built, providing a new concert hall and home for the Brno Philharmonic.

If it wasn't for this strange emotional mist from my inherited brain and the blood circulating round me in the youth of majestic nature! The emotions make the composer; not as scientifically as an emotional fund. I'm amazed by the thousands and thousands of rhythms from the worlds of light, colour, sound and matter, and it makes my tone younger through the eternally rhythmic youth of eternally youthful nature.

Apparently alive for seventy years! Celebrate it. In a letter from Písek I read, "Why not, then, celebrate the fact that you were born?"

A View of the Life and Works (1924)